Writing materials

Papyrus

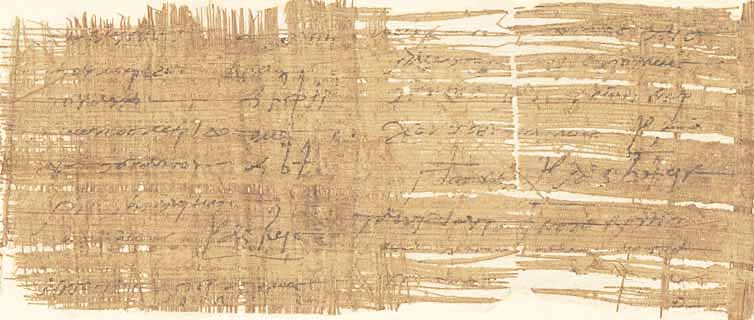

Papyrus was the most important writing material in antiquity. Papyrus scrolls were produced since the 3rd millennium BCE from the papyrus plant native to Egypt and distributed throughout the whole Mediterranean and beyond. For the manufacturing of papyrus, the pith of this grass species is cut into strips a few centimeters wide, layered crosswise, pressed and dried. The resulting sheets (selis, pl. selides) were then glued together (kollesis) forming scrolls that were several meters long in some cases and around 30–35 cm high. Today the inner side of a scroll (resp. the side written first) is called recto and the outer side verso. Plinius the Elder provides in his Naturalis Historia a short overview on the manufacturing process of papyrus sheets in antiquity. He distinguishes different quality degrees of papyrus, which differed in price, too.

Ostraca

Potsherds (Ostrakon, Pl. Ostraka) offered a low-priced alternative to papyrus as writing material. Especially damaged or no longer used clay vessels like amphorae, vases or tableware were broken into smaller pieces and used to write short texts. Although in some cases entire amphorae have been written on, this material is generally suitable for short texts because of its weight and fragility. For the most part ostraca contain instructions, short letters, lists and accounts, receipts for taxes or deliveries, furthermore school texts and other semi-literary and literary texts.

Wooden and wax tablets

Although in Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall hundreds of texts written on thin “woodsheets” have been discovered, belonging to the military context of this fort, wood in Egypt was seldom used as writing material. In fact wood was quite scarce in Egypt, whereas papyrus and ostraca were available anytime. Nevertheless, spectacular texts on wood are preserved, for example from the ad-Dachla Oasis in the West Desert. Wood was moreover a common writing material for the text genre of mummy labels.

Parchment

Parchment is produced from the untanned skin of sheep, goats or calves. According to an ancient legend, parchment has been “invented” in Pergamon (today Bergama in Western Turkey) in the 2nd century BCE, as King Eumenes II wanted to build up a library which could compete with the Alexandrian one. The Egyptian King Ptolemy V prohibited thus the exportation of papyrus to Pergamon. This circumstance led to the invention of parchment as a substitute for papyrus. Whatever the historical truth behind this story might be, parchment played a subordinate role to papyrus throughout Antiquity. While papyrus was easily available also outside Egypt, the production of parchment was more complex and therefore more expensive. This situation begun to change slowly in Late Antiquity, when parchment started to be used for the production of splendid Codices which gradually substituted the papyrus scroll as privileged book form. Furthermore the collapse of the Western Roman Empire as well as the Arabic conquest of Egypt made the export of papyrus to the West even more difficult. As a consequence parchment became in the Middle Ages the main writing material for precious codices, followed later by paper for everyday texts.

Other writing materials

Besides papyrus, potsherds, wood, wax tablets and parchment every other surface has been used in Antiquity for writing purposes as long as it was available and suitable for a given text. Therefore texts have been preserved also on animal bones, small stones, lead tablets or house walls.

Ink and writing tools

Ink was normally used to write on papyri, ostraca and wooden tablets. The most common ink was a mixture of soot, water and Arabic gum. Besides this there were other types of ink, for example inks containing iron. Colors were added with parsimony. Little canes, whose tips were made soft and fibrous by chewing them, or sharpened reeds (kalamos, pl. kalamoi) were used as writing devices. On wax tablets letters were carved using metal styli (Latin stylus, Greek graphos). These styli had in most cases a sharpened tip for writing and on the other side a widened and flat end to smooth the wax surface again.