SM I 10 (P. 21165)

We all know this stressful situation: it all starts with an elevated temperature, you feel weak, then you get hot and cold… You have caught the fever again and your plans for the next few days go down the drain. How nice would it be if you could get rid of the fever in the blink of an eye by using magic or if you could not get sick in the first place? The writer of this magical papyrus probably thought the same. It is a magical amulet that is supposed to protect a person called Tuthus from fever and chills.

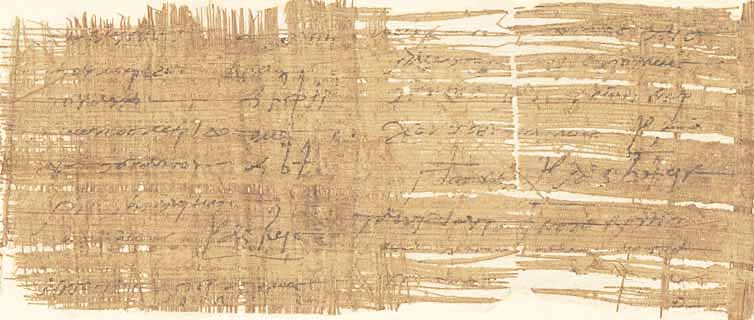

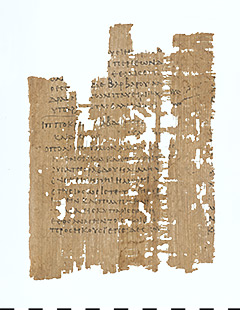

The papyrus fragment, dated to the 3rd–4th century AD, probably comes from the Fayum, a large oasis south-west of Cairo. In ancient times, the area was also known as Arsinoites and was one of the agricultural centres of the country. The papyrus has a light brown colour and is characterised by a dark discolouration on the left side. It is also damaged at all edges and has been folded three times horizontally and seven times vertically. This suggests that the papyrus formed a small package, which Tuthus may have worn on a string around his neck (this was often the case with amulets and protective symbols in Ancient Egypt). The magic symbols and the Greek magic words – in a large font slanted to the right – are found on the recto (front). The verso (reverse side) is blank. The amulet is made up of several components:

On the upper edge of the papyrus, there are two parallel lines of magic words. The first three words of the first line, „Adonai“, „Eloai“ and „Sabaoth“, are Hebrew names of god, angels and aeons. As the terms were ascribed a powerful and mighty meaning, they were frequently used and can often be found together on magical amulets.

It is similar with the two following words „αβλαvαϑαvαβλα“ and „ακραμμαχαμαρι“. They are also of Semitic origin and were used very frequently in magical texts. In the case of the former, this is mainly due to its structure. Αβλαvαϑαvαβλα is a misspelling of αβλαvαϑαvαλβα (ABLANATHANALBA). This is a palindrome, i.e. a word that reads the same forwards and backwards. Such words, especially αβλαvαϑαvαλβα, were repeatedly used in magic texts, as it was believed that reading words backwards would break the spell. Palindromes were used to prevent this and increased the spell even further if a person tried to break it by reading it backwards. As αβλαvαϑαvαλβα was regularly used on gems together with solar deities, the word is attributed a solar meaning. Another possible meaning of αβλαvαϑαvαλβα is „Father come to us!“. However, meanings of palindromes should be viewed with scepticism, as they were primarily formed to mean the same thing when read backwards and forwards. The different spelling of the word on the magic papyrus is probably a mistake. It is unlikely that the author intended that the protective spell could be broken. It seems more likely that he was unaware of the palindromic nature of the word. This phenomenon was not uncommon, which is why αβλαvαϑαvαλβα is actually very often misspelled on magical amulets.

Αβλαvαϑαvαλβα frequently occurs together with the word ακραμμαχαμαρι (cf. line 1). Ακραμμαχαμαρι (AKRAMMACHAMARI) is composed of the originally different magic words ακραμμα and χαμαρι. As the word was often used in connection with the sun, for example in another magic text as the name of the Greek sun god Helios respectively the sun at the third hour, ακραμμαχαμαρι is also ascribed a solar meaning. However, it was not used exclusively in this context and, like many other magic words, stood for power and strength in a more general sense. The same applies to the first word of the second line „σεσενγερβαρφαρανγης“ (SESENGERBARPHARANGĒS), which was often used together with ακραμμαχαμαρι.

This magic word is followed in the second line by the seven vowels of the Greek alphabet: αεηιουω. They are also common for magical texts and are usually interpreted as the seven classical planets, which are all visible to the naked eye and have been known since ancient times. These are the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

After the seven vowels, the writer again made use of powerful words to unfold the magic. The first word „Iao“, another name of the Hebrew god, was used on many magical Greco-Roman amulets because of its power. It can also be found once more in the second line (penultimate word). The second word „Φρη“ (PHRĒ) stands for Re, which is Egyptian for „the sun“.

On the left-hand side of the magical amulet, below the two initial lines, there is a column consisting of six lines. In the first line, there are again the seven vowels, while the other five lines each contain an angel’s name, which is supposed to serve as a protective spell. The angels mentioned are predominantly archangels, i.e. angels of a higher status. They are mentioned one below the other in the following order: Uriel, Michael, Gabriel, Suriel, Raphael. Among them, Michael, the archangel with the highest reputation, is regarded as the angel of peace as well as the helper and protector of people before God and on earth. The archangel Gabriel stands for mercy and justice and is regarded as the bringer of good news. Archangel Raphael has the power to heal, which is also reflected in the meaning of his name „God heals“ or „Healer of God“. The author of the text trusted in all these powers of the angels and therefore invoked them to protect Tuthus from the fever.

To the right of the column, a so-called „uroboros“ can be seen. This is a serpent, sometimes a dragon, that bites its own tail. Uroboroi were frequently depicted on magic papyri from Hellenistic Egypt. The word is made up of the Greek terms „οὐρά“ (OURA) for tail and „βορός“ (BOROS) for devouring and therefore means „tail devourer“. As it devours and simultaneously begets itself, the uroboros primarily stands for eternity as well as infinity and symbolises the universal cycle of power consumption and power regeneration. Therefore, it also symbolises nature, recurring time, the year and the course of the sun, the moon, the sky and the universe. Self-sufficiency is another characteristic of the Uroboros: its body forms a closed circle, the most perfect of all shapes. It is independent of perception and locomotion, as there is nothing around it. It also needs no food, as it consumes its own faeces and itself. The circle of the Uroboros on the magical amulet is filled with another common magic word: „σεμεσιλαμ“ (SEMESILAM). It extends over two lines and stands for „eternal sun“ or possibly „shining sun“ in Hebrew. Below this word, separated by a line, are the seven vowels once again.

From the uroboros, the line continues to the right. It is intersected by a cross, three S-shaped parallel lines, a straight line and another cross, which are „signa magica“, which means „magic signs“ in Latin. One of these is the so-called „Chnumis sign“ (also known as the Chnouphis sign or Chnubis sign). It consists of a horizontal line that is crossed by three S-shaped lines. The lines represent snakes. The symbol is associated with the serpent-shaped god Chnumis and the creator and Nile god Chnum, who can also appear as a serpent. In Greco-Roman times, the snake symbolised rejuvenation and the continually renewing year, as it sheds its skin. The Nile was also imagined as a snake, as its flood initiated the new year and the associated renewal. Bearers of amulets with depictions of Chnumis or with a Chnumis sign hoped that they would benefit from the regenerating power and thus solve their (health) problems.

The line with the signa magica ends on the right in an elongated oval filled with further magic words. The term in the first line and the first word in the third line are parts of a formula used in other magical amulets. The Greek letter „Zeta“ (Z) can be seen three times in the middle line, each time crossed by a horizontal line. This could be a symbol of the planet Zeus and Jupiter respectively.

On the right-hand side, there are five lines of magic words with a border around them. The border is in the shape of a „tabula ansata“. The term is Latin for „tablet with handles“ and refers to a rectangular inscription tablet with lateral attachments, which was popular in antiquity. Its purpose was to emphasise the inscription. The words of the magic papyrus bordered by the tabula ansata already appear in the first two lines in the same or in a slightly modified form: αβλαvαϑαvαβλα, αχραμμαχαμαρι, σεσενγενβφαραγης, Iao, and Sabaoth. The first word in the last line of the tabula ansata is made up of „ωρι“ (ŌRI) for „great is Re“, referring to the ancient Egyptian sun god, and „φερ“ (PHER), which was used as the beginning of several magic words.

Below the signa magica, the oval and the tabula ansata is a prayer addressed to the gods and angels, which can be translated as follows: „Protect Touthous, whom Sara bore, from all shivering and fever, tertian, quartan, quotidian, daily or every-other-day. Eloai angel Adônias Adônaei, protect…“ The time indications do not refer to the hoped-for protection, as one might think, but to the fever. This probably refers to the so-called swamp fever/intermittent fever (malaria), which spread in the Mediterranean region in ancient times. Already back then, there were different types, which were differentiated according to the frequency of fever attacks. The naming of the mother in the prayer is also worth mentioning. In Egyptian magic, it was customary to give the name of the mother rather than the father after the recipient of the spell.

The magic papyrus is a very detailed and meaningful example of the magical amulets that were popular in Ancient Egypt and during antiquity. They were worn on the body (like our magic papyrus, often as a necklace) and were intended to bring luck, protection and healing to the wearer. To do this, the magician sought help from deities, angels and other saints and charged the amulet with magical formulas. This becomes very clear in the case of our amulet: the writer repeatedly invokes mighty and powerful words, deities and angels, elements of astronomy as well as symbols of regeneration and eternity to unfold the magic and activate the protective spell. Amulets with spells against fever and chills were quite common. There were also many for clear vision or with love spells. Even newborns were given magical amulets for protection. However, they were intended to protect not only in this world, but also in the afterlife and therefore were buried with the dead. Amulets have survived to this day and are still (occasionally) worn as lucky charms. Ancient amulets such as this magic papyrus are therefore important, as they allow us to trace the development and long tradition of magical and protective amulets.