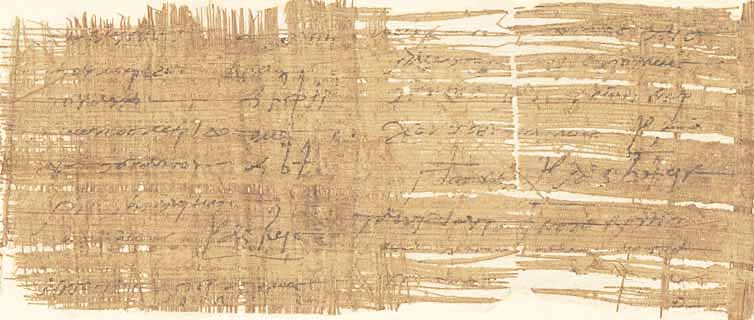

BKT IX 90 (P. 11754 + P. 21187)

“Men are pigs” is a phrase often uttered by women when they have been treated disrespectfully by men, be it through infidelity, selfishness, ruthlessness or abusive behavior. This topic is very old and was already addressed in ancient times. A literary treatment can be found on this papyrus.

The fragments of this papyrus were found during Otto Rubensohn’s excavations in Eschmunen, the ancient city of Hermupolis in Middle Egypt. They are written on both sides and come from one sheet of a papyrus-codex that was probably also written in Hermupolis. The script is a relatively large book script, slanted to the right, which can be dated palaeographically to the 6th century AD. A lower margin about 5 cm wide is preserved on both sides. Although all the other pages of the leaf have not survived, the size of the original paper can be reconstructed. There were probably 34 to 35 lines on each side.

The ink is brownish, apostrophes have been added occasionally and accents etc. are missing. It is interesting to note, however, that another scribe has made slanted strokes in the upper part of the lines, first in brown and later in black ink. They indicate where a word ends or a new one begins. This information was very helpful, as not all words were written separately as they are today. Instead, all letters were written one after the other without spaces. Punctuation marks were also not used. These slanted strokes should therefore be regarded as a reading aid.

The text contains a small excerpt from Homer’s “Odyssey”. Homer was and is the most famous poet of Western culture. He wrote the two epics that are known today as the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey”. These works were probably written around the turn of the 8th and 7th centuries BC, with the transition from the Mycenaean culture to the classical Greek period. Even in ancient times, he was the most respected poet in ancient Greece. His works were read, copied and studied again and again. They have served and continue to serve as inspiration and the basis for epic adventures, fantasy and dramatic media.

The Odyssey is about the adventurous wanderings of the king of Ithaca, Odysseus, who is returning home from the ten-year Trojan War. The 10th canto, to which the text on the fragmented papyrus leaf belongs, is about the failure of Odysseus and his crew to reach their homeland and almost all of his ships are destroyed by the Laestrygonians. They finally land on Aiaia, the island of the sorceress Circe. The experiences on the island are described in the text of the papyrus leaf.

To explore the island, a group of Odysseus‘ companions roam the surrounding area. When they soon arrive at the sorceress’s palace, they are surprised by tame wolves and lions. Circe entices and seduces her guests with a sumptuous meal. However, she spiked the foods and drinks with a poison and turned the men into pigs with a swing of her rod. Only the suspicious Eurylochus did not fall for the trap. He quickly returns to the ship to tell Odysseus what has happened. Despite Eurylochus‘ resistance, Odysseus immediately sets off to rescue his companions. On the way, he meets the god Hermes, who offers him his help.

The text of the papyrus breaks off at this point, but we know the rest of the story. Odysseus forces Circe to reverse the transformation of his men into pigs, thereby saving them.

Let us return to the main question: whether men are pigs or not. It’s a colloquialism and a question of perspective. The important thing is, are we talking about all men or about a certain category of men? And perhaps only about those who behave like pigs in one way or another. Besides, women can be no different and this question can also be applied to them.