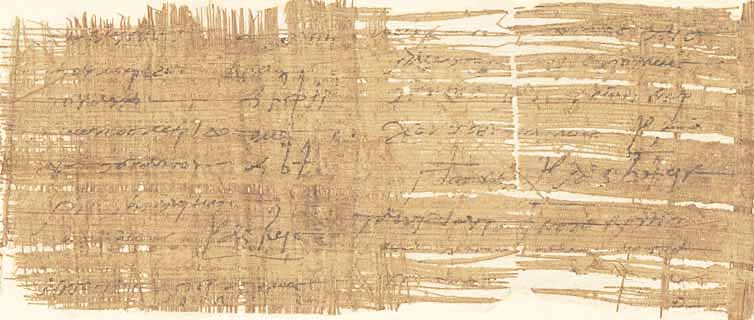

P. 14283

Ordinary people have their wills written by a lawyer. Ancient poets, however, wrote theirs themselves, namely in verses. Is this the case here and is this a testament by the famous epigrammatic poet Posidippus of Pella, who is named here, or did someone else try their hand at being a poet under the guise of a well-known name?

The poem begins with an invocation of the Muses, the goddesses of the arts. Addressed with epithets and referencing the poet’s earlier works, they are called upon to sing about the ‘hated old age’ along with Posidippus. The request for assistance in writing a poem was a common practice in antiquity, based on the belief that the Muses inspire and guide poets.

They are asked to descend from their vantage point on Mount Helicon and come to „Pipleian Thebes,“ where the writer is presumably located. This reference, however, poses a riddle because no geographically specific place with that name is known. There is a Thebes in Greece and one in Egypt, but neither is directly associated with the epithet Pipleian or Pimpleian (as it is more frequently called). In some versions, Pimpleia is the mother of the Muses, and in others, it is their birthplace. Here we can only speculate. However, it is clear that the poet has chosen a metaphorical level to describe his location.

The following verses are hard to interpret because they are placed at the very bottom of the first column of the tablet and are very worn down. But again, the name Posidippus is readable, and a reference to the god of poetry, Apollo, is inferred. The second column speaks of an oracle, which the god had once given in favour of another poet from Paros, thereby granting him honor. A poet who might fit this comparison is Archilochus of Paros, to whom, according to tradition, an honorific temple was built after his death at the command of Apollo. Posidippus asks for something similar and wishes to be honored beyond the borders of the city and country. He also has a specific idea of how this should happen, namely, through a statue depicting him holding a scroll, placed in a busy marketplace. Such a statue could be awarded in antiquity either during one’s lifetime or posthumously as a special honor.

He continues with the poet comparison and speaks of the ‘Nightingale from Paros’, who always causes sorrow and tears. The nightingale is a bird often associated with poets, as it sings its songs just as the poet his verses. This likely refers again to Archilochus, known for his satirical and ruthless writings. In contrast, Posidippus’ works do not bring the audience to tears. However, what exactly they are supposed to bring is lost in the faded verses at the bottom of the wax tablet.

The poem ends with a prayer-like formula in which the author expresses the wish to pass away in old age as a benefactor to society, walking upright and speaking clearly—healthy in both body and mind—and to leave his house and possessions to his children. Thus, a happy departure from life. How does this relate to the previously mentioned ‘hated old age’? Perhaps it is not to be taken literally, but rather as a thematic collection of poems, of which this one is part, serving as an introduction to the various facets of old age.

The wooden tablet comes from Western Thebes (Egypt) and is dated to the 1st century AD, while the content—the engraved poem—seems to fit the socio-political conditions of the 4th or 3rd century BC. This was also the time when the aforementioned epigrammatic poet Posidippus of Pella lived, who, after studying philosophy in Athens, spent some time on Samos before moving to the Ptolemaic court in Alexandria. This supports the assumption that he is the actual author of the poem.

The original poem was likely used as a writing template or transcribed from memory, rather than composed as an impromptu imitation. This accounts for the numerous spelling mistakes that have crept into the text, some of which were corrected or worsened by the writer himself. He often confuses long and short vowels, struggles to differentiate between the i/e sounds, which were still clearly distinguished in classical pronunciation, and is unsure about case and personal endings. Greek was probably not his first language.

In contrast, the well-formed letters point to a practiced hand. However, the script changes in the middle of the second column of the front side, and the writing shifts to a more cursive style. The uneven division of the front side is also noticeable: in the first column, the writer left a lot of space for the verses, occupying two-thirds of the writing surface, while the second column took up only the remaining third. This forced him to keep the letters compact and occasionally extend words beyond the wax, onto the wooden edge. There was enough space on the back, but only the last four verses are written there.

The writing medium, the wax tablet, is especially known from educational contexts. It is ideal for notes and exercises because the wax can easily be smoothed out with a metal stylus and rewritten. Thus, it is somewhat ironic that the poem, which is only preserved on this wax tablet, can be understood as a kind of legacy.