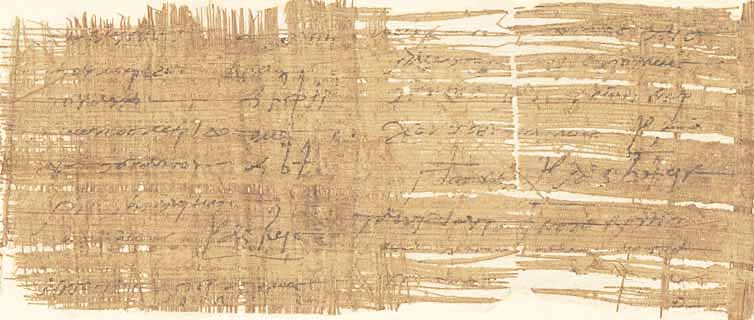

BGU III 953 (keine Inv.Nr.)

We have probably all written a shopping list at some point. Very few people think that this piece of paper could be found and examined many centuries from now. Nikon, the author of this order of herbs, certainly felt the same way. Unfortunately, the precise examination of the papyrus, which would certainly yield a lot of information, is no longer possible. Unfortunately it burned, along with other papyri, in a fire in the port of Hamburg in 1899.

Ulrich Wilcken and Heinrich Schaefer found this piece and several others during an excavation commissioned by the General Administration of the Royal Museums in Berlin from January to March 1899. The excavation took place in Ehnâs-Heracleopolis, which was located west of the Nile in Middle Egypt near today’s Ehnasya el-Medina, 15 kilometres west of Beni Suef. Ulrich Wilcken copied the list and some other papyri on site, which means that at least their contents are known. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that these copies were made by Wilcken with the idea that he could improve them later (when dealing with the pieces in more detail), which is why they cannot simply be viewed as perfect copies of the writings contents.

After these copies were made, many of the finds were loaded onto a ship in the spring of 1899. The ship was supposed to bring the approximately 80 boxes of papyri (two boxes of which already contained 250 layers of smoothed papyri wrapped in plant paper) safely to the port of Hamburg. From there it was planned to bring most of the load to Berlin. Unfortunately, shortly after the ship arrived, a fire broke out, causing the entire cargo to burn.

Thanks to Wilcken’s copy, we know that the papyrus consisted of six lines. The first line probably referred to the sender or the person who ordered, namely Nikon. The following five lines each consisted of an herb and a quantity, which was located to the right of the product and written out in full. In addition to the copy made, Wilcken dated the piece to the 3rd/4th century AD.

Just as we measure milk and flour in different units today and usually write them down on our shopping lists, you will also notice different measurements on Nikon’s order. In the second line of the list, the measure of five weight staters is used, which corresponds to approximately 8g. Staters were actually coins, but in addition to being used as a means of payment, they were also utilized as weights. Since the weight of coins has changed over time, but not staters as a unit of measurement, it is no longer possible to convert them reliably to today’s weight. In addition to the stater, the ounce is also used as a unit of measurement in Nikon’s order. This unit of measurement appears in lines two, four and six and corresponds to approximately 30g each. In the fifth line, the obol is listed as a unit of measurement.

To the left of the units of measurement were written various herbs. Andrea Jördens and Antonio Riccardetto translated these from Greek as follows: In the second line of the list, there is talk of Malabathron or Cinnamomum malabathrum, in the third of Costus or Costus arabicus and in the fourth, of Cassia or Cinnamomum iners (a type of cinnamon). The fifth speaks of Sesel, which can be understood as both Tordylium officinale and Blupleurum Fruticosum (“Shrubby Hare’s Ear”). Andrea Jördens assumes the second meaning. Back then, this herb as well as the others in the order, was apparently obtained from the southern and eastern trade. Finally, balsam woods are mentioned in the sixth line.

Two of the five herbs are easily identifiable as medicinal herbs, as there are some recipes for remedies from this period. On the one hand, the Costus arabicus, whose root was used as a versatile medicine, for example as a remedy for “knocks” (presumably fever).

On the other hand, the herb “spiral ginger” or Bupleurum fruticosum also appears in some recipes. It is believed that the present order is of spiral ginger, which may have been imported from Nubia. In addition to the use of the branches of this herb in worship, it sometimes was used for eye remedies, for uterine pain, for sunburns, to promote menstruation and so on. After Jean-Claude Goyon examined the Blupeurum in detail, he attributed to it a pain-relieving and antispasmodic effect due to its coniine content.

The three other herbs, however, are not necessarily known as medicinal plants. Although, some mentions and descriptions can be linked to two of the three plants. Some texts mention a spice that could be associated with cassia or cinnamon. For example, it is mentioned as a raw material imported from Punt (Somalia). In the Ebers Papyrus it is described as looking like “beans of Crete”, which unfortunately hardly helps with identification. However, some recipes mention parts of the plant, such as the root, the sawdust or flour and the wood. These parts can be associated with the cinnamon tree. The plant is used in different ways. The wood, for example, can be used to make the smell of clothes or the house more pleasant. The “sawdust” can be applied externally with other ingredients, to revitalize the vessels. Moreover, the roots are known as a chewing agent against tooth abscesses and to promote gum growth. When describing the embalming of the deceased, there might be a mention of cinnamon, which prepares the corpse with other fragrant herbs. The balsam wood, which is mentioned in the sixth and last line of the order, is unfortunately not specified in more detail. Most people talk directly about balsam or the “sap of the balsam tree”, which suggests a kind of resin product. The balsam wood or the balm is preferably used in products for the eyes. It is usually mixed with black eye make-up (mixture with galena) and other mineral substances.

A medical benefit of Malabathron cannot be ruled out, but a specific recipe or documentation of a specific application is not yet known of.

About the value of the individual plants in the 3rd/4th century AD nothing more precise can be said, although the import of the listed merchandise alone certainly had its price.

Although most of the herbs on the list have a medical use, their quantity and their different applications indicate that this is actually only an order and not a recipe nor a prescription. This means that we can deny Wilcken’s assumption that it may have been a recipe for a magic potion.

The importance of this single list may not seem very significant by today’s standards. But this piece harbours many unsolved mysteries. Is it actually a list, and if so, for what purpose? Who was Nikon? Had he perhaps invented a new cure? Was he researching something specific? Although this piece raises so many questions, it is valuable. It could give us, in conjunction with other lists and recipes, an impression of how rare and valuable some herbs were. It could also give us a clue which trade relationships were necessary for their procurement and perhaps how their meaning and value has changed over time. Therefore, this piece forms another small part of an infinite mosaic of information about the past.