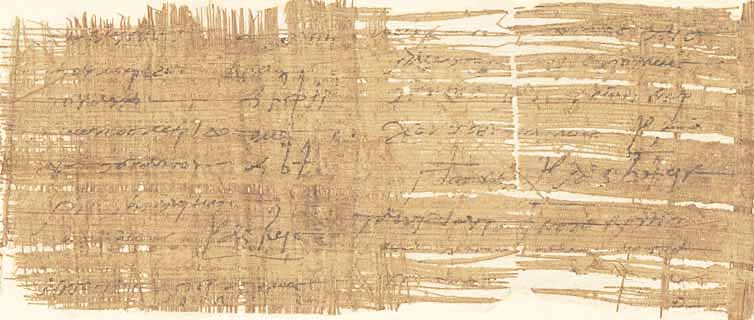

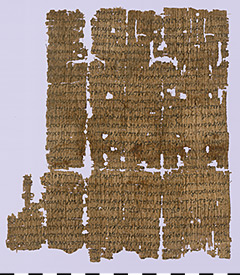

BGU III 717 (P. 7976)

“Money or Love?” – Even in ancient times, the act of marriage was one of the most important events in human life. Sometimes the conditions of a marriage were regulated by a marriage contract. A striking example of such a document is the marriage contract between Ammonios, the groom, and Iulia Terzia, the mother of the bride, from the 15th July 149 AD, which survived fragmentarily on papyrus.

Right at the beginning the exact nature of this document is mentioned. It is the copy of the marriage contract which was originally issued twice. At the end of the document it becomes clear to what purpose this copy was made. There the beginning of the application for public registration of this marriage contract is preserved, whereby the document got a strengthened legal force. However, it was valid even without this registration.

It is interesting that this marriage contract between Ammonios and Iulia Terzia was concluded between the groom and the mother of the bride. This is unusual only at first glance. Although marriage contracts could be concluded directly between the bride and groom, they usually were represented by their fathers or other male guardians if they were not legally mature. For Iulia Terzia an exception existed that is explicitly mentioned in the contract. She was allowed to act without guardian according to Roman custom, because she apparently had given birth to three or more children. This custom had been introduced by the Roman Emperor Augustus as part of his comprehensive and strict family and moral policy.

In this contract the receipt of the dowry is acknowledged and arrangements for the alimony of the bride during the marriage and the return of the dowry in case of a divorce are made. The future husband had to take care of the bride’s keep according to his financial means. The bride’s mother, however, contractually guarantees an annual supply of 12 artabas of wheat. For the return of the dowry, the conditions also known from other marriage contracts apply. The original valuables should be returned. For clothing, the bride has the choice between the clothes and the estimated value. Everything else should be returned in the condition in which it is due to daily use.

The dowry is given in great detail. For one part, the actual dowry, the exact value of a total of 1100 drachmas is given. It contains four different sets of clothes in white, purple and blue-green-shimmering color, each of which consists of two or three pieces and has a value of 140 to 400 drachmas. In addition, the bride brings with her 100 silver drachmas and gold in the form of jewelry, the exact weight of which is no longer preserved. The second part is listed without indication of value. It contains further items of clothing (e.g. five coats, a belt made of leather of a wild donkey), various items (e.g. an Aphrodite statuette, a lamp, various vessels, a cosmetic box) and furniture (e.g., boxes, baskets and chairs).

For the validity of a marriage it was not necessary nor even common that a marriage contract had to be drawn up between the future spouses (or their legal representatives). Nevertheless, more than 100 marriage contracts have survived from Greco-Roman Egypt, not only attesting the marriage, but also providing interesting insights into various aspects of conjugal life.