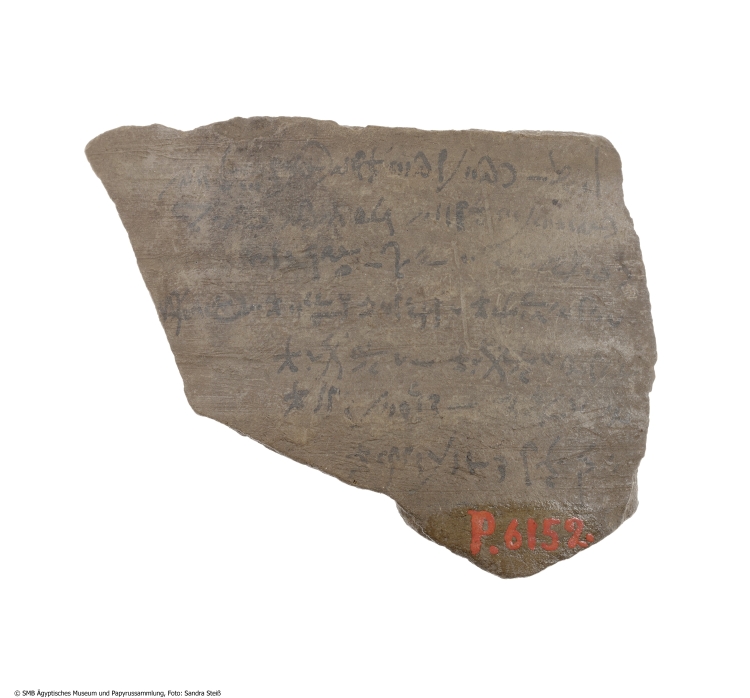

P. 6152

What did ancient Egyptian horoscopes look like? Was there a difference to Greek horoscopes? How did such a horoscope work? The Demotic ostracon published by Otto Neugebauer and Richard A. Parker in the end of the 1960s represents the most typical type of horoscope from Egypt, a so-called basic horoscope. Like most texts of this kind, it was written on a potsherd, while Greek equivalents were typically written on papyrus.

A horoscope is a text providing astronomical information used to predict someone’s future, and a basic horoscope contains only the essentials. Typically, it records the date and time of birth, not the date of writing. This information appears in the first two lines. According to the text, the individual for whom the horoscope was cast was born during the fifth nocturnal hour, in the night between the 23rd and 24th of Phamenoth, under Emperor Nero. The text refers to him as Nero Claudius Caesar. The date corresponds to 27 February AD 57, and the hour indicates a birth about one hour before midnight. The text, however, could theoretically have been written at some point even decades later in the life of the person born on that date.

Had the scribe used the Alexandrian calendar, introduced after the Roman conquest of Egypt, the date would fall in mid-March on the Julian calendar. Instead, the astrologer noted the birth according to the traditional Egyptian ‘wandering’ calendar, which lacked a leap day. Each year was 365 days long, causing the calendar to drift by one day every four years. While this seems appropriate for a text written in Demotic, also most ancient astronomers in the Greek-speaking world relied on the Egyptian calendar for their calculations.

After the date, the planetary positions are recorded. Ideally, the astrologer listed seven positions: the luminaries – sun and moon – and the five planets known in antiquity. These were usually given by zodiac sign, beginning with the sun, then the moon, followed by the five planets in order of perceived distance from Earth: Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury with the first mentioned planet taken to be the furthest away.

Often, however, positions were not given on separate lines. Instead, the scribe grouped celestial bodies in the same sign on one line, saving ink by writing the sign name only once. In this case, the sun, Mars, Venus, and Mercury were in Pisces; the moon and Saturn in Taurus; and Jupiter in Gemini.

These positions were calculated rather than observed. For a horoscope like this, the astrologer likely consulted a text such as the Berlin papyrus P 8279, a sign-entry almanac listing the dates on which planets entered new signs over several years. With such a resource, the astrologer could easily look up a date and record it on a potsherd like on this ostracon. Forecasts were then derived from another type of manual, an astrological handbook. An example of such a text has been described here.

Planetary positions alone were insufficient. The astrologer also needed to note the zodiac sign rising on the horizon at birth, the ascendant. In Greek, this point is called the ‘horoskopos’, which gives us the modern term ‘horoscope’. The ascendant was the most essential element of this type of text, and the genre was named after it. The ostracon states that the ascendant was in Scorpio.

Its significance lay in serving as the starting point for converting astronomical data into astrologically meaningful factors, such as domiciles and lots. How that transformation occurred, however, is a story for another time.