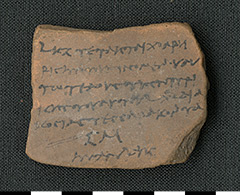

SB IV 7401 (P. 12560)

In this text a person with the name Choareris, whose name is not mentioned in any other Greek text from ancient Egypt, received a receipt for the payment of 240 drachmas for a tax on natron of the current year. At the beginning of this text the exact year is mentioned: the 27th year of a Ptolemaic king. Even though the name of this king is not mentioned, it can be deduced with some certainty from the rather high regnal year and the palaeography of the text that it must have been the 27th year of Ptolemaios VIII., which lasted from 28th of September 144 BC to the 27th of September 143 BC. When exactly in the course of this year the tax was paid by Choareris is not mentioned in the text. In the last two lines the amount of money is repeated in Greek numerals and the receipt is signed by an Apollonides, who most likely had been an official person from a bank, who was in charge of countersigning and confirming such receipts. The entire text of this receipt is written in the same handwriting which makes is most likely that it was written by the Apollonides who signed it at the end.

It remains unclear from this receipt alone why there has been a tax on natron. But the pure existence of such a tax already shows the importance of natron and makes it very probable that the Ptolemaic state could receive substantial revenues through this tax and presumably also through monopolizing the exploitation of natron. But also the importance of natron and its use cannot be explained through this text. Fortunately, other receipts of payments for the natron tax in the Papyrus Collection in Berlin offer some more hints. In one text a small addition is made to the name of the tax showing that it is the natron for the laundry. Another text confirms the payment of the natron tax on behalf of the fullers. These little hints show that the tax is for natron which was used for the laundry and similar work. This might have been the greatest use of natron during this time but it was also used for salting meat and the mummification of corpses as Pliny the Elder and Herodot tell us.

The text of this receipt was written on a potsherd, which is then called ostracon. As a writing material it was available everywhere and therefore very cheap. This ostracon came to light during the excavation of Friedrich Zucker in Elephantine in the campaign 1907/1908. Since the ostracon was found in Elephantine it is most likely that the receipt was also written there, even though a place name is not mentioned in the text.