BGU IX 1900 (P. 11642)

If you have ever been annoyed by the high rent of your apartment, house or land, then you are basically no different from the people of ancient Egypt. Already at that time pieces of land were leased to citizens. However, the rent for such a piece of land was often way too high to be paid by a single person. Since many of the poorer citizens were dependent on such an area to be able to feed themselves and their families, they joined together to form so-called lease cooperatives. In these leasehold cooperatives, the land was then divided between the individual leaseholders. The tenant used his land to earn agricultural profit from it, for example, as a farmer. This profit, however, had to be ceded mostly to the ruler. Nevertheless, for many of the poorer citizens it was the best way to ensure their survival. Even today there are still some lists of such lease cooperatives. The following text deals with exactly such a list.

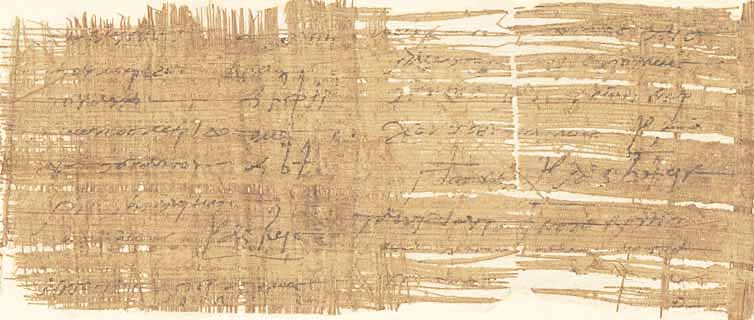

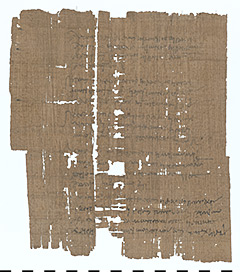

The papyrus is not an ordinary sheet, but a roll which is 160×23 cm in size and apparently also completely written. The text came to the Berlin Papyrus Collection in 1912/13 by an exchange from the London British Museum. However, the text was written around 196–198 AD in Theadelphia, a Greek village in the Arsinoites, the modern Fayum. The age and place of manufacture of the scroll could be determined because the strategos Bolanos is mentioned in the text. It is already known from other documented sources that he lived around 196 AD. Moreover, there is a relationship with another text, which is housed in Belgian Ghent nowadays. The production of this text is also dated to 196–198 AD in Theadelphia. The other piece is also a list of tenant cooperatives, partly mentioning the same people as in the Berlin piece. Therefore, a relationship between the texts is also suspected, where one also assumes that the Berlin piece is the older of the two texts.

The list includes 50 leasing cooperatives with their members, and the size of the leased land is also added for each cooperative. However, the members are not listed in alphabetical order, which indicates a topographical arrangement. This means that the members were probably sorted according to their place of residence. The number of members, in the individual leasehold cooperatives, varies from case to case. The most common is seven members, which is the case in 28 of the 50 listed leasing cooperatives. The remaining 22 cooperatives all have between five and nine members. On the other hand, there are not so many differences in the size of the leased land. In 41 cases, exactly an area of 80 arouras is leased, one arouras being equivalent to 100×100 royal ells at that time. In the remaining nine cases, the area is always slightly smaller or larger than 80 aruras. However, this balances out in the end so that the total area is about 4000 aruras. But it cannot be concluded exactly from the text whether it is a single large area or several smaller ones. This results from the fact that the text gives a location only in the 154th line and this line is apparently only loosely connected with the rest of the text.

The purpose of the piece is not entirely clear, as there is no indication in the text of how much land each tenant was entitled to. A possible explanation for this is that the list was created only as a directory of leasehold cooperatives and their members. From today’s point of view, the text is nevertheless very informative. Since in the list not only includes farmers, but also other occupations such as fishermen, miller or shepherd, it offers a good insight into the economic and social conditions of ancient Egypt.