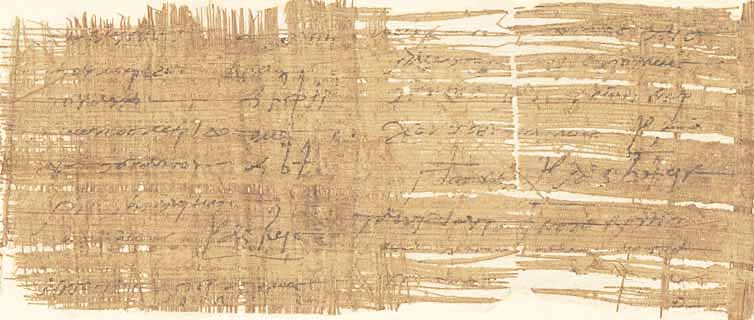

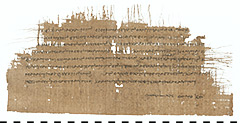

BGU VI 1297 (P. 13999)

This private letter from a certain Zenon is part of the largest archive from Ptolemaic Egypt. But who is behind the many names, what is this letter about and where are the places mentioned in this letter?

The letter was purchased by Carl Schmidt in the spring of 1912 for the Berlin Papyrus Collection. It was probably found in an excavation site near today’s Umm el-Baragat, the ancient Tebtynis. This site is located southwest of Cairo in the oasis of Fayum, which in ancient times was called Arsinoites and was divided into three parts. In the eastern part, the Herakleidou Meris, was the place Philadelpheia and in the southern part, the Polemonos Meris, the ancient Tebtynis.

The papyrus is written on both sides. On the front, the recto, is the text of the letter, on the back, the verso, the address, which remained visible even after the letter was folded. The letter is quite well preserved except for a few places. Zenon’s writing is strictly stylized and secure and shows a skilled, professional scribe.

Zenon was born around 285 BC in Kaunos, a city in the southeast of ancient Asia Minor. Later he came to Egypt and became a wealthy and influential businessman in the middle of the 3rd century BC. Initially he was the private secretary of the dioiketes (finance minister) Apollonios. Later he became administrator of the estate of the same Apollonios in Philadelpheia in the Arsinoites. His archive was also found there, of which more than 1800 texts such as letters, petitions and lists, but also recipes, contracts and literary texts are still preserved. It was in this context that the letter to be presented here was written by Zenon on 16 November 248 BC, as the date at the end of the letter indicates.

In this letter Zenon writes to a certain Phanias. First he greets Phanias, hopes that he is well and says that he himself is well. Then he asks him to give a horseman permission to leave his post. Unfortunately the name of the horseman is no longer completely preserved. Only the end –achos can still be read. Zenon now explains why this horseman needs this permission. Nikandros, the horseman’s father, has been arrested. The reason is not given, but it is assumed that Nikandros had financial difficulties. The son now wants to sail to Alexandreia, in order to stand up for his father with the dioiketes Apollonios and to ask for his release.

The horseman of this letter belonged to the group of Greek soldiers to whom the state assigned a piece of land, a kleros. On the one hand, this was intended to provide them with food and also served to cultivate large areas of land that had not been used until then, especially in the Arsinoites. On the other hand, these soldiers had to remain available as a military reserve. The letter now shows that as the owner of such a kleros, one was obviously obliged to be present. From other documents of that time we also know that a longer absence could well be punished with penalties, e.g. the confiscation of parts of the kleros. In his distress, the aforementioned horseman now turns to Zenon, whom he considers to be so influential that his support is very helpful in getting a permission from Phanias to be absent.

Phanias and Zenon seem to know each other well. From other letters in the archive it is clear that they are even close friends. In addition, we learn from other documents that Phanias held the office of scribe of the horsemen and thus had extensive authority and influence in theArsinoites and beyond. He was not only responsible for the mustering and swearing-in of the soldiers and the horses, but also supervised the proper cultivation of the assigned land and its surveying. This also included approving possible absences.

As with most letters, also this letter of Zenon to Phanias can only be correctly understood in the context of the other letters, since much information was known to the writer and the addressee and, therefore, did not have to be mentioned again. But for us this information is important in order to understand the letter correctly. In this respect we are lucky that so many texts have been preserved from the Archive of Zenon. Nevertheless, we unfortunately do not know whether the horseman mentioned in this letter was given permission to sail to Alexandria to stand up for his father.