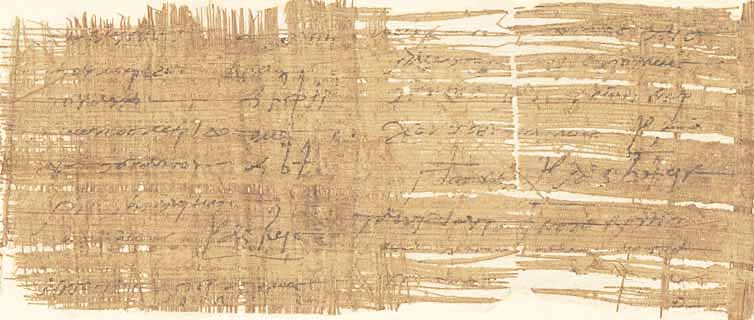

P.Schubart 16 (P. 7508)

Who would not like to know more about their own future and destiny? This was also the case in ancient times. Therefore, people used horoscopes. The papyri have left us with large numbers of original horoscopes. But these usually consist simply of records of the positions of planets and zodiac, not analysis. How were the data from these horoscopes interpreted? Apparently, usual practice was not to commit the interpretation to writing, at least not on the same sheet as the data, but to convey them orally, or in other written forms now lost to us.

But fragments of other papyri in Greek, representing original compositions as well as translated Egyptian, can be recognized as belonging to handbooks that would have guided to this interpretation. The treatises took the form of verse as well as prose. One influential poem, preserved in multiple witnesses on papyrus as well as citations in authors on astrology whose work has come down to us in the medieval manuscript tradition, is attributed to the Egyptian astrologer Anoubion, an important early witness to the circulation of Egyptian astral knowledge in the Greek language. Not much is known about his life. He probably came from Thebes and lived in the second or third century AD. He wrote an introduction to astrology and horoscopes in verse, which survived in fragments. He is probably the same person that is mentioned in writings which are wrongly contributed to Clement of Rome, the second or third successor of Petrus as bishop of Rome. In these writings a certain Anoubion of Diospolis, the Greek name of Thebes, is called an associate of student of Simon Magus, a Gnostic magician and first heretic of the church in the first century AD.

In this papyrus, which does not mention the name of Anoubion at all, the identification of his work is supported by the characteristic use of the elegiac distichs, a meter that consists of a dactylic hexameter followed by a dactylic pentameter. This meter was widely used in antiquity but is unique to him among surviving astrological poetry. The use of verse may have served a practical, mnemonic as well as decorative function.

The author speaks here in the first person as our “guide,” and he mentions the Sun as “master” in some connection to sexual desire (erōs), along with technical terms from astrology such as kentron, a group of zodiac signs of special significance defined by the Ascendant and its three counterparts at right angles along the zodiac.

The remains of a single column on this papyrus give us unfortunately little connected sense, though the papyrus remains a valuable supplement to the eight other papyrological witnesses to the fortunes of Anoubion’s work in the centuries after he wrote, before his disappearance from the medieval canon.