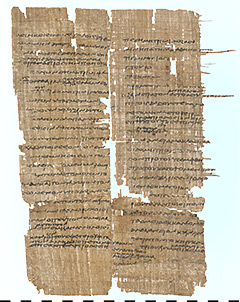

FGrHist 533 F 2 (P. 11632)

Who can name all Seven Wonders of the World, let alone say, when and why they were built? With the Colossus of Rhodes, a papyrus can help us to understand its creation.

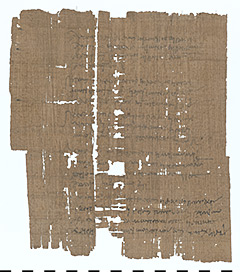

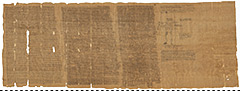

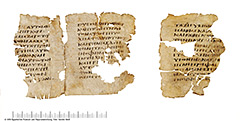

The papyrus was found in the village of Mellawi. Mellawi is in Upper Egypt, in the ancint administrative district Hermopolites. In 1912, the piece was bought by Wilhelm Schubart, who was the director of the collection at the time, alongside other pieces. The papyrus contains a literary text in Greek, which is dated to the 2. Century AD. In the 2. Century AD Egypt was under Roman rule.

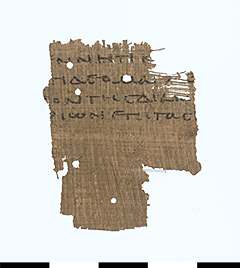

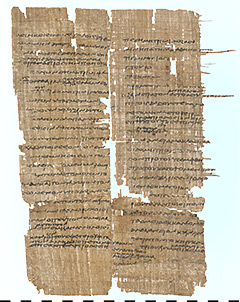

The text consists of two columns with 24 lines each. It is historical prose and written in the ionic dialect. This could be because that was the dialect customary for historical writing. This convention exists because the first Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote in ionic. The text deals with an episode from the Wars of the Diadochi. After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC his followers, the Diadochi, fought over supremacy. Rhodes, too, was dragged into this conflict, which our piece reports.

The island Rhodes with the city of the same name is situated off the coast of Asia Minor. Originally, it was part of the Persian Empire, then, however, it fell under the influence of Alexander the Great. After Alexanders death, the island tried to stay independent and neutral. This worked for a while, but then the diadoch Antigonus subjected the whole of Asia Minor. Because of the spatial closeness, Rhodes was forced to help him. Several times, Antigonus demanded assistance from Rhodes. When they refused and also repulsed his fleet, he sent his son Demetrius Poliorcetes to Rhodes for a punitive expedition. This was in the year 305 BC. Very fittingly, the name Poliorcetes means besieger of cities.

In the first phase of the siege, he set up camp outside the city walls and blocked the city from the outside world. Demetrius then tried to breach the wall. 304 BC he could take the first circle of walls. However, the Rhodians had a second wall, behind which they could withdraw. When Demetrius broke through this second wall, the Rhodians had built a third one in the meantime.

But this one too Demetrius managed to breach eventually. Before he conquered the city completely, he aborted the siege, because he was called to help against Cassander by some Greeks. He made a peace treaty. The Rhodians thanked their patron, the sun god Helios, by building a colossal statue at the port. It is known today as the Colossus of Rhodes as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. So, one of the Seven Wonders of the World has a siege as history.

Diodorus, who wrote a historical work in the first century BC, is the one who predominately informs us about the siege of Rhodes. But our piece, too, is a source. Because our author and Diodorus write so similarly, the question arises whether our author copied Diodor or whether they both had the same source. Since they differ in terminology, the latter is more likely.

Our piece covers only a part of the siege of Rhodes. The beginning possibly is about the Rhodians capturing clothes which the wife of Demetrius sent him, because royal things are mentioned. Then the Rhodians refuse to release prisoners of war, even though Demetrius offers ransom. Therefore, he announces that he too will not release Rhodians in the future. Next, it is described how Demetrius tries to breach the first wall. He bribes Athenagoras of Milet, who was on the side of the Rhodians, to help him. He reveals the plan to the Rhodians. So, the Rhodians start to dig as well, and Demetrius’ plan fails. Additionally, Athenagoras handed over to the Rhodians a follower of Demetrius, Alexander. Athenagoras is rewarded and Alexander is saved from execution in the last moment by ransom.

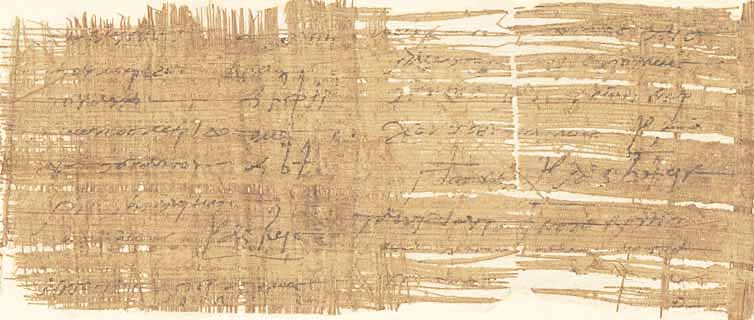

What makes our text special, is the fact that it is an autograph, meaning the handwriting of the author himself. This can be recognised by the fact that the text is a draft. Again and again, words are crossed out, partly because of grammatical errors, partly because the author wanted to choose different words. We can watch the author work, so to speak. Autographs are extremely rare. Another specialty is the word μεταλλωρύχος. It is a Hapax legomenon, which means it attested only once.

The first editor of the text, von Gaertringen, concludes his essay with: “May the Egyptian soil offer more of such finds!”.