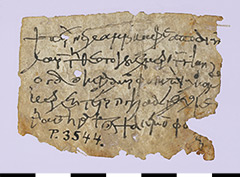

BGU II 676 (P. 3544)

ATTENTION!! This piece from the Berlin Papyrus Collection is not papyrus. Instead, it is parchment! This „papyrus database“ comprises mostly papyri, but also parchments, paper, wood, pottery sherds, wax tablets and inscribed textiles. But what is parchment and how does it differ from the other writing supports?

Parchment is non-tanned animal skin, mostly from goats, sheep or calves. Before writing on it, the hair and the last remnants of flesh had to be removed, then the skin was dried and stretched. Before writing could begin, the skin was smoothed with pumice stone and whitened with chalk. The parchment was first written on the flesh side – which is smooth, in contrast to the hair side, which has pores and is rougher.

The parchment presented here from the Berlin Papyrus Collection is quite well preserved. The five lines of Greek text are almost complete. Only a few letters are missing at the end of the last line, but these can be deduced from the content.

But how did this piece come to Berlin? It is certain that the parchment arrived in the Berlin collection between 1877 and 1881 and probably came from the Fayum, an oasis southwest of modern Cairo. The Fayum was one of the agricultural centres of the country in ancient times. The parchment probably belongs to the so-called „1st Fayum find“. This contained texts, much of which came from the rubbish heaps excavated since the late 1870s near the ancient city of Arsinoiton Polis. Arsinoiton Polis was the capital of Fayum in antiquity, which was then called Arsinoites. The finds have come onto the antiquities market and are now mostly kept in Vienna, Paris and Berlin.

But now to the content of the text on this parchment. It is a receipt for the payment of the poll tax. Many details of this tax are unfortunately unclear, as the available sources, such as the receipt presented here, allow valuable insights, but still never make clear the entire system behind it. In the period from which this parchment comes, one had to pay two nomismata (the currency of the time) for the poll tax. As a rule, it was paid in two instalments.

One learns from the text of this parchment that a dyer named Neilammon paid an instalement for the poll tax of 1 and 1/4 keratia. A keration was a smaller unit of currency and was equal to 1/24 nomisma. The amount paid is therefore relatively small. Moreover, the receipt reports that this was the third instalment for the poll tax. This may explain the relatively small amount of money, but it is exceptional. No other receipt for the poll tax of that time mentions such a third instalment.

In addition, the receipt states that Neilammon did not make the payment himself, but used a certain Aurelios Phoibammon to do so, who was probably a slave of a Kolluthos. Paying taxes by a representative was not uncommon and is frequently mentioned in the texts. At the end of the parchment, another person with the name Phoibammon confirms this payment with his own signature.

This receipt contains one more piece of tax-relevant information: the tax year and the day of payment. The instalment was paid for the so-called 8th indiction on the 15th of Choiak (an Egyptian month). The indiction was a 15-year cycle for counting tax years that had been used since the 4th century in the Roman Empire and thus also in Egypt. The years within the cycle were simply numbered consecutively. The people of that time were of course aware of which index year they were living in at the time. However, a conversion to the calendar used today is impossible without further clues. Based on the writing, the text can be dated to the 7th to 8th century and thus belongs to a time when Egypt had already been conquered by the Arabs and belonged to the caliphate. At least the receipt tells us that the payment was made on the 15th of Choiak. This corresponds to 11 or 12 December – depending on whether it is a leap year.