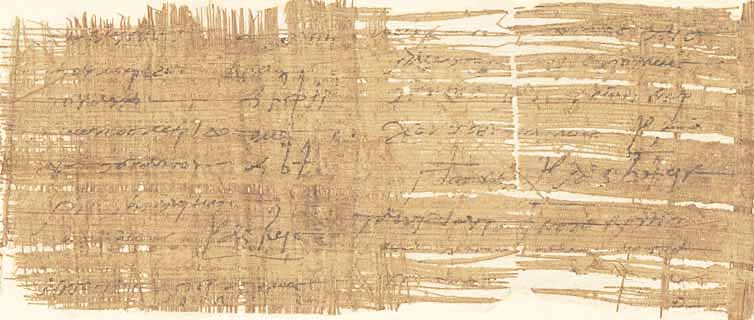

BGU III 726 (P. 7788)

Buying at the right time has always been a good deal. This is true today and was also the case 1500 years ago. This also seems to be the case with a business deal that the text on the papyrus presented here gives us some insights into.

This papyrus was found by the Africa explorer and botanist Georg Schweinfurth in 1886 during his survey of the ruins of the ancient Arsinoiton Polis, which was the name of the modern-day Medinet el-Fayum in late antiquity and Byzantine times. It was and is the main town of the Fayum, a large oasis south-west of Cairo. In the same year, Schweinfurth donated this papyrus fragment, along with many others, to the Berlin Papyrus Collection, where it was soon also scientifically evaluated.

But Schweinfurth was not the only one to find artefacts in these ruins at that time. It is therefore not surprising that there is a papyrus in the Vienna Papyrus Collection that fits directly with the Berlin fragment. All that is known about the Vienna fragment is that it was found in the Fayum in the late 1870s and early 1880s. There is no connection to Georg Schweinfurth. But from the fact that it belongs with the Berlin fragment, it can be concluded that it must also have come from the ruins of Arsinoiton Polis.

The two fragments together contain the upper and middle part of a document that records a loan of money. The bottom part, with the signatures of the two parties to the loan and of the notary, is missing. The two fragments can be joined together with a small gap in between, so that they overlap in line 12 of the text. The letter Kappa of the last word in the first line of the Berlin fragment has its upper end on the bottom edge of the Vienna fragment. The back of both fragments shows particularly well the vertical lines. They show that the document was folded horizontally three times. Vertical folds are to be assumed at the places where the fragments broke apart.

The document was created on 19 October 481 AD, as indicated by the dating formula in the first two lines of the Vienna fragment. In addition to the Byzantine-era dating by tax years, the consul of the current year is also given. Both can be converted to our current calendar.

In this document, Aurelius Paomios from the village of Philoxenou in the Herkleidou Meris in the east of the Fayum and Aurelius Olympion from Arsinoiton Polis agree that Paomios will receive money from Olympion in the amount of one gold solidus minus four keratia, and in return, Paomios will give him flax in seven months‘ time, in the amount of the loaned money plus interest in the form of three artabas (about 90 kg or a donkey load) of wheat. The repayment is to take place in the month of Pauni, at the end of the harvest season. The text also indicates that both parties had apparently made a similar agreement in the past. Perhaps Paomios and Olympion are even regular business partners.

In this business relationship, in which the sale of natural products and a loan of money were combined, both parties seemed to profit. The farmer probably used the money to live on until he could earn income again by selling his agricultural products. The lender was apparently interested in the flax. Moreover, a clause in the contract protected him against inflation. The quantity of flax was to be calculated at the price that flax was worth at the time of repayment, which was the current market price. It is likely that the prices for natural products were much lower during the harvest than they were half a year before or after. In addition, Olympion secured the product early on, which he either needed himself or wanted to use for further business transactions. Finally, he could demand much higher interest rates when repaying a loan in natural products than if he received the borrowed money back as money. Interest rates of up to 50% are known. It was not until the 6th century that they were limited to 12.5%. If the loan was repaid in money, only 4% could be demanded. Apparently a good deal.