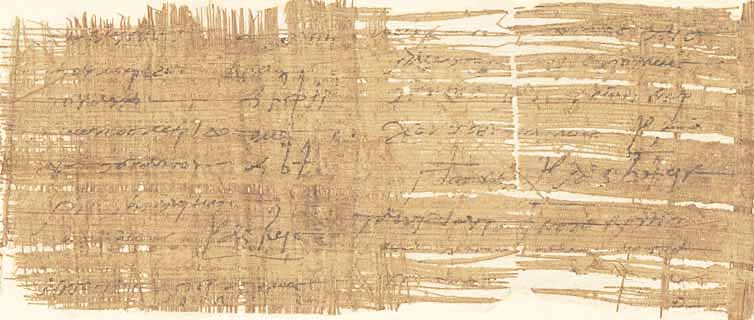

BGU XIII 2253 (P. 21448)

We all know that cute donkey from the petting zoo, with the fluffy ears and the friendly „hee-haw“. However, few people know that its ancestry goes all the way back to the wild donkeys of Ancient Egypt. Unlike today, donkeys in Ancient Egypt were not stroked. Instead, the domesticated donkeys were used as beasts of burden and the wild donkeys were hunted.

This piece is about such a wild donkey hunt. This is a receipt for assistance in hunting wild donkeys. In it, the state hunter Dionysios acknowledges to the elders of Soknopaiu Nesos that their workers supported him in the hunt for wild donkeys. A note indicates that Lukios, son of Anubion, received the receipt.

The aforementioned Soknopaiu Nesos is now known, as Dimê It is no longer an inhabited city, but an archaeological site. It is located in Fayum in Egypt, about 3 kilometres north of Lake Qārūn and 35 kilometers west of Kōm Aushīm.

The receipt consists of 15 lines of Greek script written on the recto (i.e. parallel to the fibres) of the papyrus. Thanks to a date in the tenth line, the papyrus can be dated to January 26, February 5 or 15, 191 AD. The place of origin of the piece is already known as Soknopaiu Nesos. The receipt therefore already contains some information, but hardly any about the hunt for wild donkeys.

Donkeys had a difficult life in Ancient Egypt. The donkey was a hated animal, mainly because it was associated with the god Seth and usually seen as his animal form. Seth was regarded as the god of chaos and destruction. The more Seth was feared in the faith, the more the donkeys, as the embodiment of Seth, were hated and despised. Nevertheless, donkeys were needed for transporting goods, working in the fields, etc. Domesticated donkeys were used for this purpose. It is not known exactly when, where and how the first donkeys were domesticated, but mentions of them date back to the 4th century BC. Wild donkeys are therefore very different from domesticated donkeys. Apart from hunting, nothing is known about other use of wild donkeys. There is information about hunts for wild donkeys but it is limited. Most insights into the possible course of such a hunt are provided by depictions in graves and prehistoric wall paintings.

Many of these depictions show a connection between the wild donkey hunt and the pharaoh. The pharaoh had many tasks. In addition to his political role, he also had a very important cultic role. Among other things, the „destruction of enemies“ and the “restoration of order” were among the pharaoh’s most important cultic tasks. The terrestrial as well as the cosmic powers were regarded as enemies. It is therefore not surprising that depictions of the hunt for wild donkeys, i.e. the destruction of the animal form of Seth, can be found in connection with the „destruction of enemies“. Despite the pronounced hatred of the donkey, it was not given a special position in hunting scenes. The donkey, especially the wild donkey, was seen as part of a whole, as part of the desert animals. This is why groups of wild donkeys usually appear in hunting scenes alongside herds of antelopes, gazelles and ostriches.

In these depictions, the pharaoh is often seen standing on a chariot armed with bow and arrow, shooting at the wild donkeys. In order to understand the probability of such a hunting scene, a few facts must be taken into consideration.

For one thing, the Egyptian chariot in question could probably reach a maximum speed of 40 km/h. The Egyptian bow had to be about 30 m to 70 m away from the target for a direct shot.

Secondly, according to evidence, the wild donkeys hunted were either the African wild ass or the Achdari, a Syrian representative of the Asian half-ass. Both species were very shy and flight-prone animals. The loud and conspicuous chariot would have startled the donkeys, which would certainly have had a head start of 200 to 400 meters. In addition, wild donkeys prefer stony ground, which is unsuitable for horses. This allowed them to reach a speed of 40 km/h to 48 km/h on a flat surface over a longer period. Half-donkeys could even reach speeds of up to 70 km/h. The speed of the donkeys is supported by reports in which people complain about the difficulty of hunting, as the donkeys would be able to outrun racehorses as well as racing camels.

The Egyptian chariot could not possibly get close enough to a donkey to give the shooter a good shooting position. The donkeys had a clear advantage with their head start and speed. Therefore, the depicted chases with a chariot in the wild are rather unlikely. This results in two possible ways of carrying out the hunt.

One is a hunt, in which the game is driven towards the pharaoh. More recent reports also suggest a driven hunt. In this case, a few beaters in front would quietly push the game out of its hiding places. The donkeys then would try to change their hiding place and run in front of the waiting pharaoh, who could have driven towards the donkeys at the right moment.

Second is the hunt in an enclosure. Accordingly, the depictions on the walls would only show an abbreviated hunt. Several references from the New Kingdom and from the beginning of the supplement to the desert hunt in Medinet Habu suggest such a hunting event.

The receipt from Soknopaiu Nesos shows that workers were needed for the hunt. This fact points to a hunting method in which a large number of people is used. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that the hunt from the receipt was a driven hunt.

The magnificent and stately depiction of the wild donkey hunt once again emphasizes its ritual significance. The hunt was not considered a pleasure, but was intended to illustrate the pharaoh’s heroism as well as his power over the enemy and his role as a sporting and healthy ruler.

The wild donkey therefore had an important influence on Egyptian culture. Its sacrifice enabled the pharaoh to underpin his position. The domestic donkey also played an important role in trade and the cultivation of the fields for a long time. The donkey, with which so many bad things were associated, therefore played a major role in the survival, prosperity and continued existence of the Egyptians.

It is in this significant context that the rather inconspicuous receipt for support in hunting wild donkeys presented here should be understood.