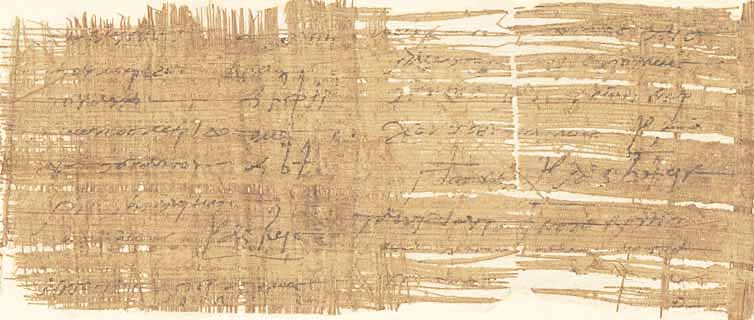

P.Eleph. 1 (P. 13500)

What motivated a couple from the Greek world to enter into marriage relatively soon after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great in the south of that country? This marriage contract does not reveal any personal motives, but it does provide direct information about legal practices, mobility and migration at the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

The papyrus P.Eleph. 1 sheds light on the earliest phase of Hellenistic Egypt and, due to its content, is one of the most fascinating documents that Greek papyrology has to offer. This is because the consequences of an epoch-making event — Egypt became part of the Greek or Hellenistic world for centuries — on a social and legal level can be traced directly and very closely to the people of the time.

“In the seventh year of Alexander, son of Alexander, in the 14th year of the satrapy of Ptolemy, in the month of Dios; marriage contract between Herakleides and Demetria; Herakleides takes Demetria, who comes from Kos, as his lawful wife, a free man a free woman, from her father Leptines, who comes from Kos, and her mother Philotis; (Demetria) brings clothes and jewellery worth 1000 drachmas into the marriage, and Herakleides has to provide Demetria with everything that is appropriate for a free-born woman; and we shall live together wherever it seems best to Leptines and Herakleides, by mutual consent; if Demetria should dishonour her husband Herakleides, she shall be deprived of what she had brought into the marriage; but Herakleides shall prove his accusations before three men who both of them acknowledge; Herakleides shall not be allowed to take another woman home and thereby insult Demetria, or to have children with another woman, or to do Demetria harm under any pretext; if Herakleides should do any such thing, and Demetria can prove it before three men who both of them acknowledge, Herakleides shall return to Demetria the dowry to the value of 1000 drachmas which she brought with her, and shall also pay 1000 Alexandrian silver drachmas; Demetria and those who assist her in demanding payment shall have the right to demand payment as if there were a judgment, both out of Herakleides himself and out of all his property by land and sea; this contract shall be valid everywhere, whether Herakleides should use it against Demetria, or Demetria and her helpers should use it against Herakleides to claim payment, as if the agreement had been made on the spot; Herakleides and Demetria shall have the right to keep the contracts separately under their own custody and to use them against each other; witnesses: Kleon from Gela, Antikrates from Temnos, Lysis from Temnos, Dionysios from Temnos, Aristomachos from Cyrene, Aristodikos from Kos.”

This is the oldest securely dated Greek papyrus, which because of its content has gone down in the history of papyrology as the “Marriage Contract of Elephantine.” The date of issue at the beginning of the text refers to the son of Alexander the Great, Alexander IV, and to the year after the satrapy of Ptolemy was installed. The latter, who as a general of Alexander the Great became the founding father of the Ptolemaic dynasty, is not yet a king here, but — as a relic of Persian imperial administration — a satrap of the still united Alexander Empire with jurisdiction over Egypt. The dates refer to the year 310 BCE: it was now just over 20 years since Alexander the Great had conquered Egypt and thus wrested it from the Persian Empire.

The text illustrates how a Greek immigrant couple entered into marriage in Elephantine on the southern border of Egypt and recorded this process in a contract based on Greek legal concepts. The form of the deed and the use of certain contractual clauses make it clear that the deed was intended to retain its validity and legal force even after further changes of location. As this is a double document in which the text of the contract is recorded in duplicate, it was not necessary to keep it in a fixed location. It also makes sense for each of the spouses to have one copy of the double document and also the right to convene a court of three men in the event of the marriage being dissolved in order to obtain a divorce with a corresponding settlement. This three-man tribunal can be convened anywhere and is therefore, like the double document itself, perfectly adapted to a life with high mobility or at least takes into account the possibility of a change of location.

The amount of the dowry indicates that the lifeworld from which the marriage contract originates is that of wealthy persons: the amount of money mentioned corresponds to the average income of several years at that time. It remains unclear why the couple had moved to Elephantine, whether they had already lived there for some time and spent the rest of their lives there. The reason for their immigration may have been trade, but a connection to the army is also conceivable, as Elephantine was the location of a Greek garrison. Regardless of this, the marriage contract of Elephantine is exemplary of dynamic migration processes that can be traced back to the conquests of Alexander the Great and brought people from all possible regions of the Mediterranean — not only Greeks, but also Macedonians and Jews — in large numbers to Egypt.