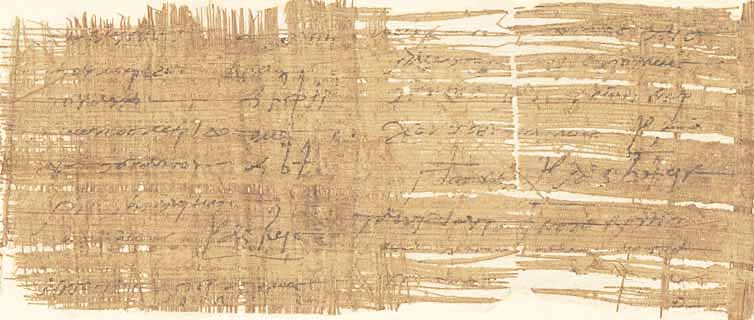

BGU I 15 Kol. II (P. 6865 Kol. II)

In Ancient Egypt, the donkey played an important role only as a working animal, it never became a sacred animal. Rather, it was a tortured animal that had to carry heavy loads, especially in the Egyptian grain transport. The second column of this papyrus fragment makes it clear that this was not only a literal burden for the donkeys, but also a burden for the donkey drivers.

The fragment comes from the Fayum, a large oasis south-west of Cairo. In ancient times, the area was also known as Arsinoites and was one of the agricultural centres of the country. The papyrus has a light brown colour and was part of a scroll. The verso (back) is blank. On the recto (front) there are two columns, each with a Greek text. The two columns are part of a register, but are by different authors. Both columns are copies of entries from official diaries. In Ancient Egypt, administrative officials were obliged to keep a daily official diary. This was usually a brief report by their secretary, which they then certified with a signature. If necessary, certain sections of the diary were copied.

Column II can be dated to July 11, 197 AD and can therefore be placed in the Roman period of Egypt. The column is a 27-lined copy of a letter containing a decree. In this letter, the praefectus Aegypti (the Roman governor) Aemilius Saturninus addresses the strategos of Arsinoites and the so-called Heptanomia (the seven middle Egyptian districts). He criticizes the poor organization of the state grain transport and blames the small number of transporters. On his repeated order, the strategoi employed the prescribed number of donkey drivers, but tolerated that they did not keep the minimum number of three donkeys per driver. Nevertheless, the donkey drivers received maintenance costs for three animals. This not only had a negative impact on the supply of grain, but also on the state treasury. The prefect therefore urges the strategoi to force the donkey drivers to keep three donkeys and to mark the donkeys with stamps so that the number can always be checked.

In Roman Egypt, grain transport was one of the most important state tasks and was closely linked to the tax system. In order to ensure that transport ran smoothly, the state had to keep track of the number of transporters and transport donkeys at all times. In the case of our text, however, an illegal agreement between the donkey drivers and the strategoi led to the latter tolerating the donkey drivers‘ fraud. The motivation of the strategoi is not mentioned in the text. It is likely that they received a share of the “surplus” maintenance costs from the donkey drivers.

Apart from strategoi and transporters, the so-called ‘sitologoi’ played a central role in grain transport. They were the leading officials of the granaries, collected grain from the farmers as a tax in kind and took care of its storage. The grain was then distributed by them to farmers as seed loans or transported to harbours via navigable canals and the Nile. From there, it was transported onwards to supply central Egyptian cities, especially Alexandria and Memphis, as well as the military, quarries and mines in the eastern desert. In most cases, land transport was unavoidable, as only a few granaries were located directly next to navigable canals. The grain transport of the fertile Fayum was particularly reliant on land transport, as it was and still is located far away from the Nile. For the land transport of grain, mainly donkeys and occasionally camels were used. Compared to camels, donkeys had the advantage that they were physiologically suitable not only for desert transport but also for oasis transport, for instance in the Fayum. They also were cheaper than camels.

For Roman Egypt, transporting grain with the help of animals required a lot of effort, as the animals had to be kept and supervised. This state task was therefore transferred to the Egyptian population in the 2nd century AD at the latest and thus became a so-called liturgy. Liturgy originally referred to the services that wealthy citizens contributed to the ancient Greek community. People depended on it because state revenues alone were not sufficient. Initially, the liturgy was not obligatory, but it was quickly seen as a moral duty. Especially in the 2nd century AD, it functioned as a compulsory service.

The liturgy concerning animals used to transport grain was known as ‘τριονία ὀνηλασία’. Through this liturgy, animals from inhabitants of villages in the so-called chora (rural Egypt) could be drafted for one year of civil service. Only people with sufficient wealth (initially 1200 drachmas, later 2000) could be called upon for the liturgy and were appointed by the village scribes. After that, the liturgists gathered with their animals at a certain place where they were assigned their transport task. For grain transport, the liturgists were usually deployed in their home village, but the animals were also often used in other villages and districts if required. This was particularly the case in the Fayum, where 38% of the donkeys used to transport grain came from other districts. After a transport to another district, the donkeys were used to transport further goods to various places along their return journey. This often took a long time, as the goods had to be reloaded onto other means of transport or other goods were added.

The donkeys, which were obliged by the liturgy to transport grain, were part of a set transport corps. If the transport could not be performed solely by these ‘public’ donkeys, the state requested other animal owners to provide their donkeys as support. These ‘private’ donkeys were in fact used for many transports, but usually only in their home town. In very rare cases, rented donkeys were used to transport grain.

According to the terms of the liturgy, liturgists had to provide the state with at least three donkeys. However, this ideal could only be fulfilled in a few cases. In the 2nd century AD, a donkey driver with two to three animals was compensated by the sitologoi with around two drachmas per day or in the form of benefits in kind. In addition, the costs incurred for transport and the costs for the maintenance of the donkeys, e.g. for hay and fodder, were covered by the state. In addition to this payment, the liturgists were possibly granted further privileges, such as tax exemption for the donkey or a monopoly right for the transport of private goods. Despite the compensation, the liturgy was usually a great burden for those affected. The donkey drivers often had to travel a long way home and were not adequately compensated for the transport. To minimise the burden, in some cases several people could share the responsibility for the three donkeys. There were also some cases in which the liturgists tried to circumvent the obligations of the liturgy. In addition to disregarding the minimum number of donkeys and embezzling maintenance costs, as in this text, there are also documented cases in which the liturgists even fled the site with their donkeys. However, some liturgists also tried to take legal action against their appointment to the liturgy. One example for this is the first column of our papyrus fragment. The column is a copy of an entry from an official diary. The text can be dated to 26 July 194 AD. It deals with a trial in which a person complains about being assigned to two liturgies in two different villages at the same time.

Liturgies corresponded very much to the Roman principle of transferring as many state tasks as possible to the population in the provinces and to the individual. Both column I and column II of the papyrus fragment provide us with important information on liturgies in the Roman period of Egypt. Column II gives us concrete evidence that selected individuals had to provide the state with at least three donkeys to transport grain for a year. Column I and II also clearly show us that some individuals appointed to the liturgy were not willing to bear the burden that came with it.