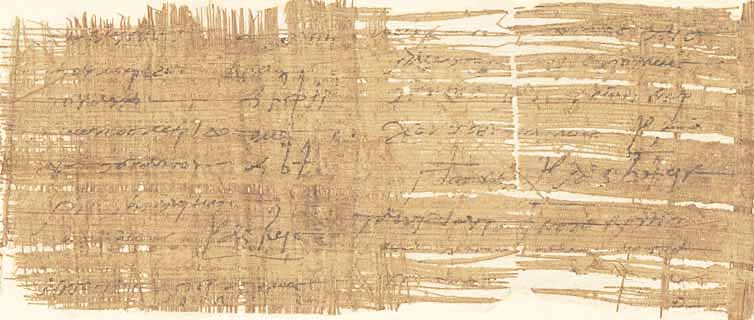

BKT III, S. 30–31 (P. 9765)

Valuable recipes are still written down today, so that they are not forgotten. This is all the more important when it comes to recipes for medicines. Even in ancient times, such recipes were written down, so that we can now gain an insight into the production of such medicines. One example is the papyrus presented here.

This fragment of a papyrus roll with instructions for a recipe is inscribed only on the front, the recto. The back, the verso, is empty at least in the part of the carrier that has been preserved. The handwriting with its large and unpractised letters shows an inexperienced scribe, can be dated to the second century AD, and points to a private copy, as the correction at the end of the fifth line of the second column also suggests, where the scribe had forgotten to add alpha and iota to καὶ and added them above the line. Only the ends of the lines of the first column are preserved. The second column is complete in its horizontal dimensions.

There are no traces of a further column. Rather, the right edge of the papyrus is an ancient cut edge and thus possibly the end of the roll. This is also consistent with the last word of the second column, which is positioned in the middle of the line at the end of a recipe instruction. This word ἔξω has been interpreted as a reference mark for the reader and should probably indicate a supplement or something similar on the other side of the papyrus. These observations lead to the conclusion, contrary to previous research, that the lower part of the columns has been preserved on this papyrus, while they are broken off at the top. Both columns end with a recipe instruction and shorter final lines, of which the end of the line is not preserved in the first column.

From the one and a half lines of the first surviving recipe instruction in the second column, we at least learn that something that was to be mixed with honey or smoothed out was to be used on an empty stomach. Since only the conclusion of this recipe instruction with hints on the use of the prepared „medicine“ is preserved here, its content remains unknown. Since the transition between these two instructions occurs in the middle of the second line of the second column, the scribe marked it on the left margin with a paragraphos, a short horizontal line under the beginning of this line.

The second last surviving recipe instruction describes the extraction and purification of beef tallow. Although nothing is known about the use of the beef tallow, it is assumed that it had a therapeutic use, as described by Galen (ca. 129 – 216 AD) at the same time. It is not excluded that this information could have been on the other side of the papyrus, to which the already discussed ἔξω refers. However, it is described in detail that beef tallow is extracted by heating the beef fat, which has been freed from the skin, smoothed and purified, in water. After melting, it is poured through a sieve under which a basin with cold water is placed. The purification of the beef tallow is achieved by repeating this process. This process is described in a very similar way by Dioscurides in the first century AD – i.e. about 100 years before this papyrus – in the De materia medica II 76, where the extraction of tallow from other animals is also described.

Even though we only have a small fragment of what was probably a fairly extensive roll with many recipes, they still allow for an interesting insight into the production of medicines in ancient times.