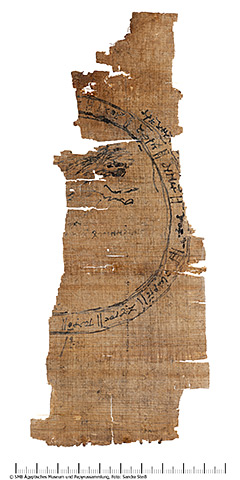

P.Kramer 17 R (P. 13102 R)

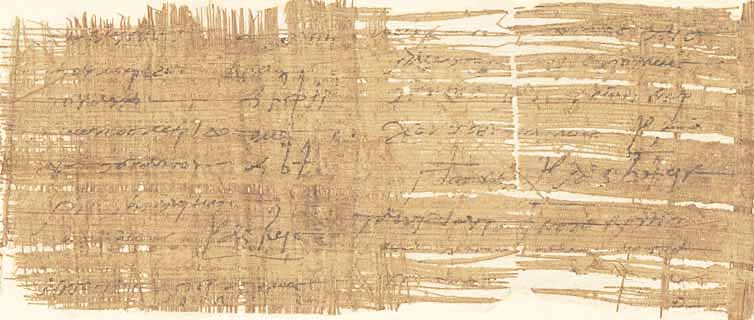

Ancient horoscopes from Egypt are most familiar on sheets of papyrus. These “original” horoscopes are attested in the hundreds in Greek and Egyptian in Roman times and complement the evidence from authors on astrology, such as Vettius Valens, who discuss example horoscopes to illustrate doctrines. Their usual form records the positions of all five planets known in antiquity (Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury), plus the Sun and Moon, in the coordinate-system of the zodiac, as well as the “Ascendant” zodiac sign, the one on the horizon at the moment in question, which gives the genre its name (horoskopos “hour-watcher” or “-marker”: the sign in this position changes on average every other hour). Forecasts based on analysis of these positions accompanies them in written form only rarely, and were probably reserved for oral communication to clients, who were also presented with the horoscope-sheets.

This papyrus, recovered from mummy cartonnage, on which the text in question is a later addition after re-use of a document, presents an unusual composite of astrological text and image, at first sight bearing little relation to the horoscope tradition. In place of the expected prose listing the planetary and Ascendant, and often giving the date and the name of the person for whom the horoscope was computed, the central element is a drawing of an animal encircled by a ring, now only half preserved, but once divided into twelve compartments to receive the Greek names of the zodiac signs. Around its edge, the names of the planets are also given, which, taken with the archaeological context of the papyrus and palaeographical considerations, allow us to determine the precise date that the composer intended to represent: between 28 December, 56 BCE and 9 January, 55 BCE. Thus, it can be taken as a horoscope after all – even if no indication of the Ascendant sign survives – and is in fact among our earliest records of such data in Greek from Egypt.

This reconstruction might suggest a draft, perhaps in the form of a cheaper version of the ivory astrologers’ boards (pinakes) attested in the archaeological record, preserving the steps by which a horoscope was computed before copying down on a papyrus sheet. The figural drawing at the center, however, and decorative features of the zodiac circle, point towards a draft of something else. We have evidence from historiography and archaeology for monumental horoscopes, more durable and public representations of the horoscopic data than the papyrus sheets. One context in which they are especially well represented in Egypt is funerary: decorations on coffins and tomb spaces that depict the planets in the zodiac signs in which they stood at the birth of the deceased, but in pictorial rather than textual form. Arguably this papyrus served as a draft for such a monument, destined to be embellished with further decorative detail, with the Greek text converted into corresponding divine figures to represent the zodiac signs and planets, rather than reduced to the plainer form of the papyrus horoscope. Decisive in this regard is the central figure, a lunging quadruped. Its pricked-up ears and fur suggest a dog, an animal associated in Roman Egypt with Sirius, whose heliacal rising in ancient Egyptian tradition (as Sothis) marked the ideal beginning of the new year – a perfect figure for the rebirth of the deceased whose funerary monument the design would have graced.