BGU VIII 1730 (P. 13802)

This papyrus contains a royal decree which regulates Alexandria’s supply with wheat and legumes. It is especially striking to see the draconic penalties for those who disobey these regulations.

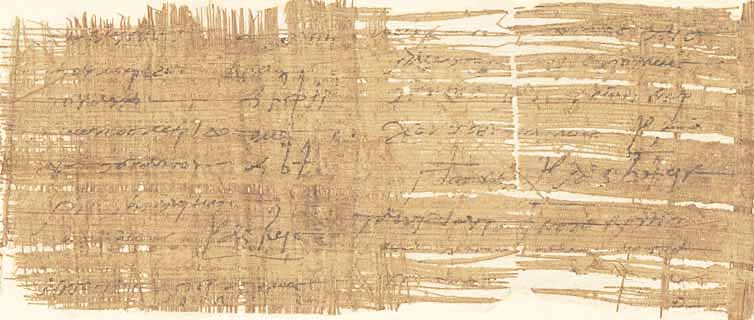

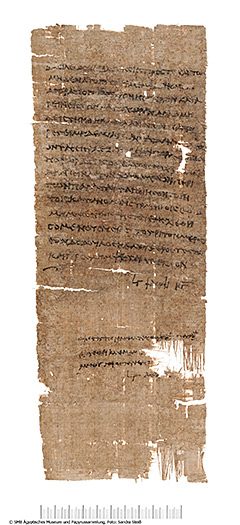

The text on this papyrus contains two parts. First, it is the actual royal decree. Secondly, below the first part and slightly intended to the right there are official comments which have been written by another person. Under the last lines of each part there are horizontal strokes, so-called paragraphoi, which indicates that the text is finished and shows that no further lines could be added. Below both part there are also separate dates: the 23rd Phaophi resp. the 5th Hathyr of a 3rd regnal year. Despite these rather precise dates the dating of the text remains uncertain, since a 3rd regnal year is not rare. The handwriting of the text can be dated to the 1st century BC and, thus, to the end of the Ptolemaic reign in Egypt. In addition, it is introduced by a formula which is common for such decrees. In this case it is the formula “Decree of the king and the queen” which allows us to limit the dating possibilities to two options: 3rd November 79 BC resp. 27th October 50 BC and 15th November 79 BC resp. 8th November 50 BC. A decision between these two options is impossible without further hints from the text.

The royal decree is rather short and starts with the regulations which are to be obeyed. They say that nobody is allowed to bring wheat or legumes from the nomes above Memphis (i.e. Middle Egypt) to Lower Egypt or the Thebais (i.e. Upper Egypt). But everything has to be brought to Alexandria, the capital of Egypt. Those who disobey these regulations face the death penalty. The aim of this decree is very clear: the supply of Alexandria with wheat should be secured. The draconic penalty for a violation of these regulations makes it very probable that the decree has been caused by an emergency situation. We know from other texts that during the 1st century BC problems with the supply with wheat have sometimes been caused by insufficient Nile floods and, thus, bad harvests. In addition, the supply of the many inhabitants of Alexandria with wheat and legumes was certainly not easy and, therefore, a big concern of every ruler, since the Alexandrians tended to riots.

The impression of an emergency situation which forced the ruler to issue such this decree is supported by the second and equally long part of this text which contains the regulations for the high rewards for informers. Everybody who informs the officials on someone who has violated the regulations of the decree should get a third of the possessions of this person. If the informer is a slave he should get a sixth and his freedom. We do not know of any slave who gained his freedom by informing on his masters, but this might be due to the scarcity of the survived texts. Nevertheless, the explicit regulations for slaves seem very clever since it was them who had a very privileged knowledge of their masters’ business. The reward might have been a high incentive for informing on them.

The separate and intended official remarks are from the office of the local official Horos and state, that a copy of the decree has been published, in fact opposite an older decree of which we do not know any details. In addition, the separate date of the official remarks show us that it needed approx. 2 weeks in order to be published in a village in the Herakleopolite nome, a county in Middle Egypt. The present papyrus with the official remarks has probably been sent back to a higher office which produced it originally.

Another sign for an official use of this text can be discovered in the lower part of the decree where almost invisible remains of a red stamp can be found. Similar stamps can be found on other papyri from this period. Usually they contain a date and the name of the office. It is very likely that this stamp contained similar information.

The present text is certainly a copy of a royal decree. This can already be deduced from the details above. In addition, the handwriting is not very elegant and, therefore, would not fit a document from a central office in Alexandria. Moreover, the present papyrus is a palimpsest, i.e. an already used papyrus has been used again. Some remains of the original writing can still be seen between the lines in the lower part of the decree and especially below its last line.

The papyrus was found in mummy cartonnage from Abusir el-Melek in Middle Egypt. The papyrus was used to make mummy cartonnage when its text was of no use anymore. The traces of writing on the back of the papyrus, the verso, could be imprints of other text, caused by the production of cartonnage.